We are in the fourth volume of the Recherche, Sodoma and Gomorra. The Baron of Charlus, in a restaurant on the Norman coast, with his usual arrogant tone, flaunts all his refined knowledge of life to dazzle and win over the young Morel:

“– Ask the Maitre if he has a Good Christian. – A Good Christian? I don’t understand. – You see, we are at the end, it’s a pear. Rest assured that Madame de Cambremer has one: the Countess d’Escarbagnas, whom she is, had one. Mr. Tibaudier sends it to her, and she says: ‘Here is a Good Christian who is very beautiful’” (Molière: *La Comtesse d’Escarbagnas*, Scene XIII) – I didn’t know that. – I see, in fact, that you don’t know anything. You haven’t even read Molière… Well, since you are incapable of giving orders, as with everything else, just ask for pears of a variety grown nearby: the Louise-Bonne d’Avranches. – The…? – Wait, since you are so inept, I’ll ask for others that I prefer. Maitre, do you have the Doyennée des Comices? Charlie, you should read the delightful page written about that pear by the Duchess Emilie de Clermont-Tonnerre. – No, sir, I don’t have that. – And the Triomphe de Jodoigne? – No, sir. – And the Virginie-Dallet? The Passe-Colmar? No? Well, since you have nothing, we’ll leave now. The Duchesse d’Angouleme is not yet ripe, come on, Charlie, let’s go.”

For us, used to choosing from the usual 4 or 5 varieties of pears at the supermarket, all this display of scholarship, with these poetic names tied to such an ordinary fruit in our perception, truly feels like a plunge into a Lost Time: a time when each region had its own local fruit production, with a thousand shades of shape, color, and taste. A biodiversity that mass consumption has completely flattened.

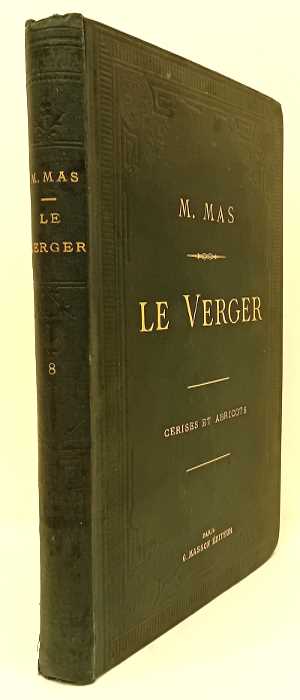

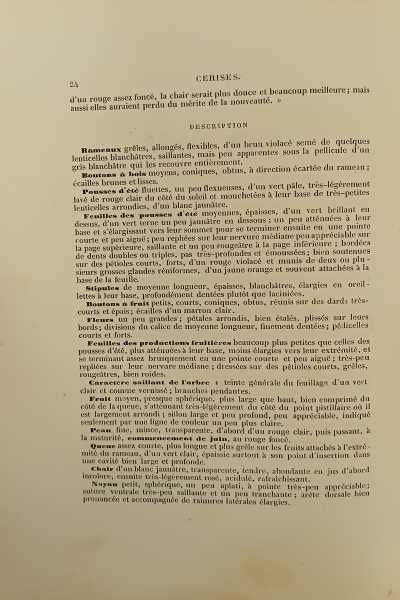

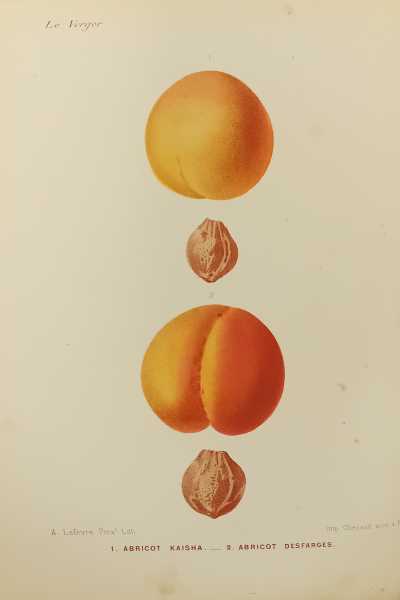

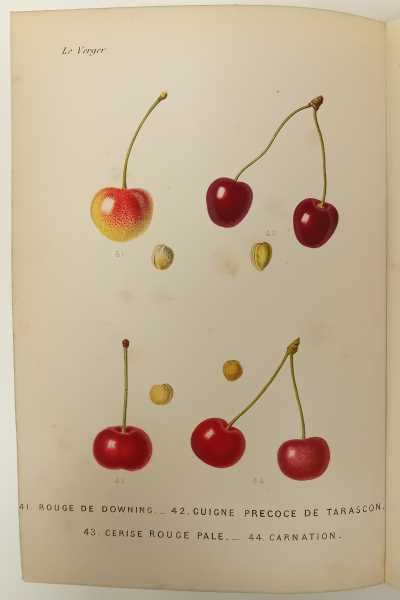

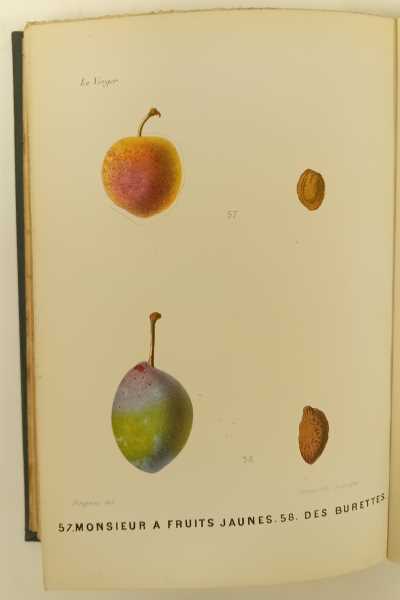

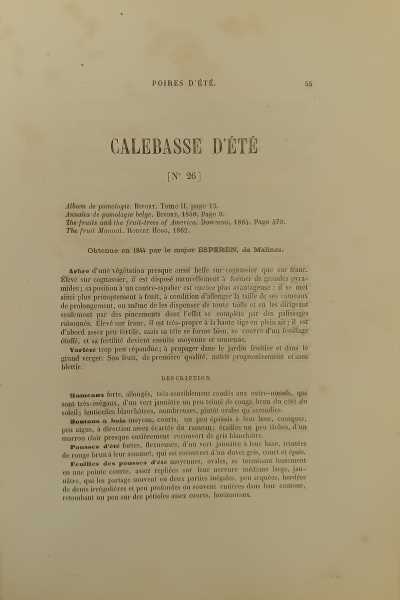

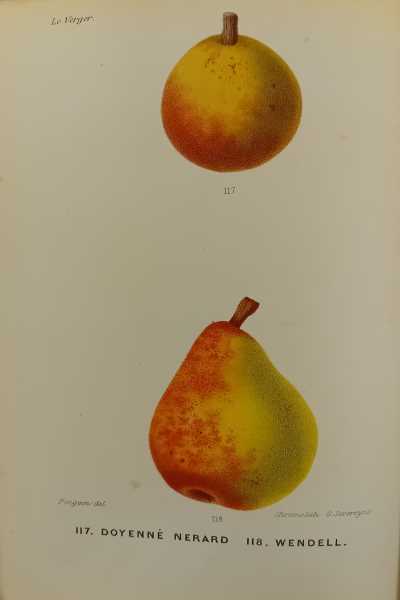

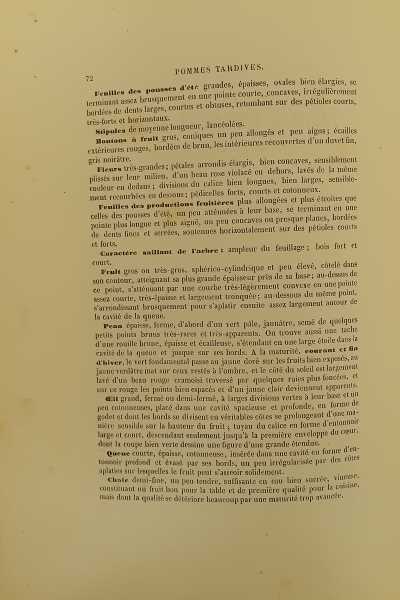

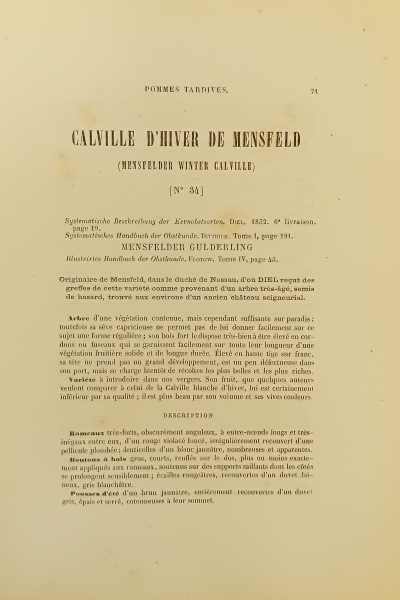

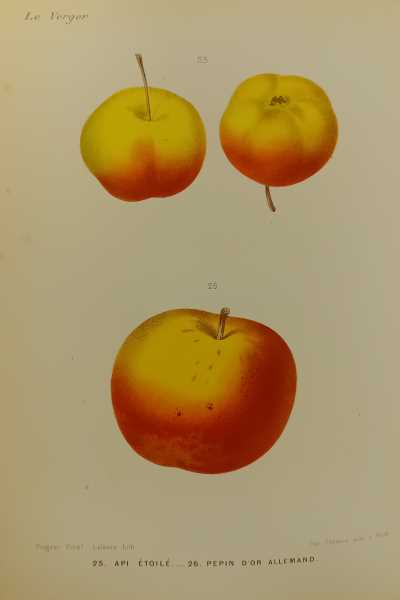

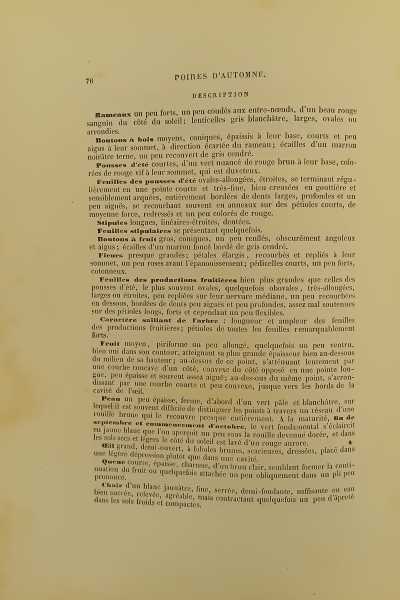

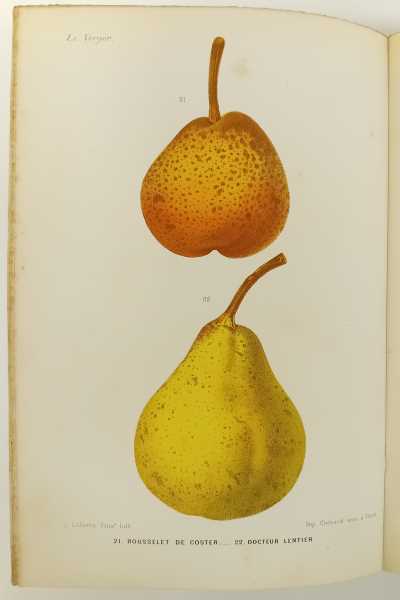

This page of the Recherche immediately came to mind when I got my hands on 6 volumes (out of the 8 published) of the work “Le Verger ou histoire, culture et description avec planches coloriées des variétés de fruits les plus généralement connues” by botanist Alphonse Mas, president of the Société Pomologique de France and the Société d’horticulture de l’Ain: an incredible list of fruit tree varieties found in Europe and North America, described in detailed cards and illustrated with chromolithographs of the fruits.

It is truly impressive the number of variations of what we simply call “apples” or “peaches”: between late and early varieties, Mas presents 120 different types of apples, and the same goes for peaches. There are 80 varieties of plums and cherries, while apricots are only 8. The creative names of these fruits often give us clues about their origins: alongside ancient species, there are regional varieties, as well as the results of research and grafting by individual fruit growers who leave their names or dedicate their discoveries to someone.

Flipping through these volumes brings a bit of sadness thinking about the fruit and vegetable stalls where we do our shopping (fortunately, a certain sensitivity to the issue finds its space in alternative circuits related to organic and local produce). And if we try to broaden our view starting from our tables, the same flattening of biodiversity seems evident in many other areas of our lives. A few examples? The loss of our own cultural roots in favor of a conformity dictated by a globalized social universe without history or traditions; the demand for those coming from different worlds to conform in the name of a peaceful coexistence that is more erasure of identities than true integration; making young people believe there is one right way to become adults (secure job, house, bank account…) without leaving room for dreams and personal quests… But perhaps we are going too far.

To return to our pears, if he weren’t so unlikeable, I would recommend to Morel to study Volume II of our Verger: 120 varieties of summer pears, to impress Baron Charlus.

We await you in our online bookstore for a feast of fruit and culture!