I don’t know who remembers a TV show that was quite popular when I was a young girl (unfortunately many, many years ago): it was called Space: 1999.

It took place in a human colony built on the Moon from which exciting space explorations began; the girls wore tight silver suits and had bobbed hair (very ’70s) in purple or blue. It was filmed in England in 1973, probably inspired by the much more brilliant 2001: A Space Odyssey by Kubrick, from 1968, with its Earth-Moon connections to the music of Strauss and its interplanetary journey to Jupiter in search of the roots of our humanity.

Was this how they imagined the transition to the 21st century in those years? A humanity already launched into the conquest of space, with technology capable of enabling the colonization of at least our satellite?

To tell the future is at the heart of all science fiction literature, but not only.

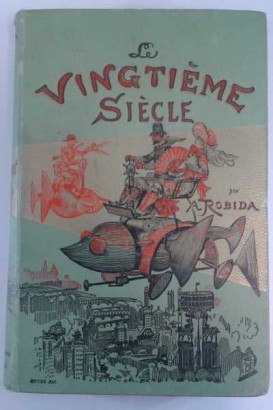

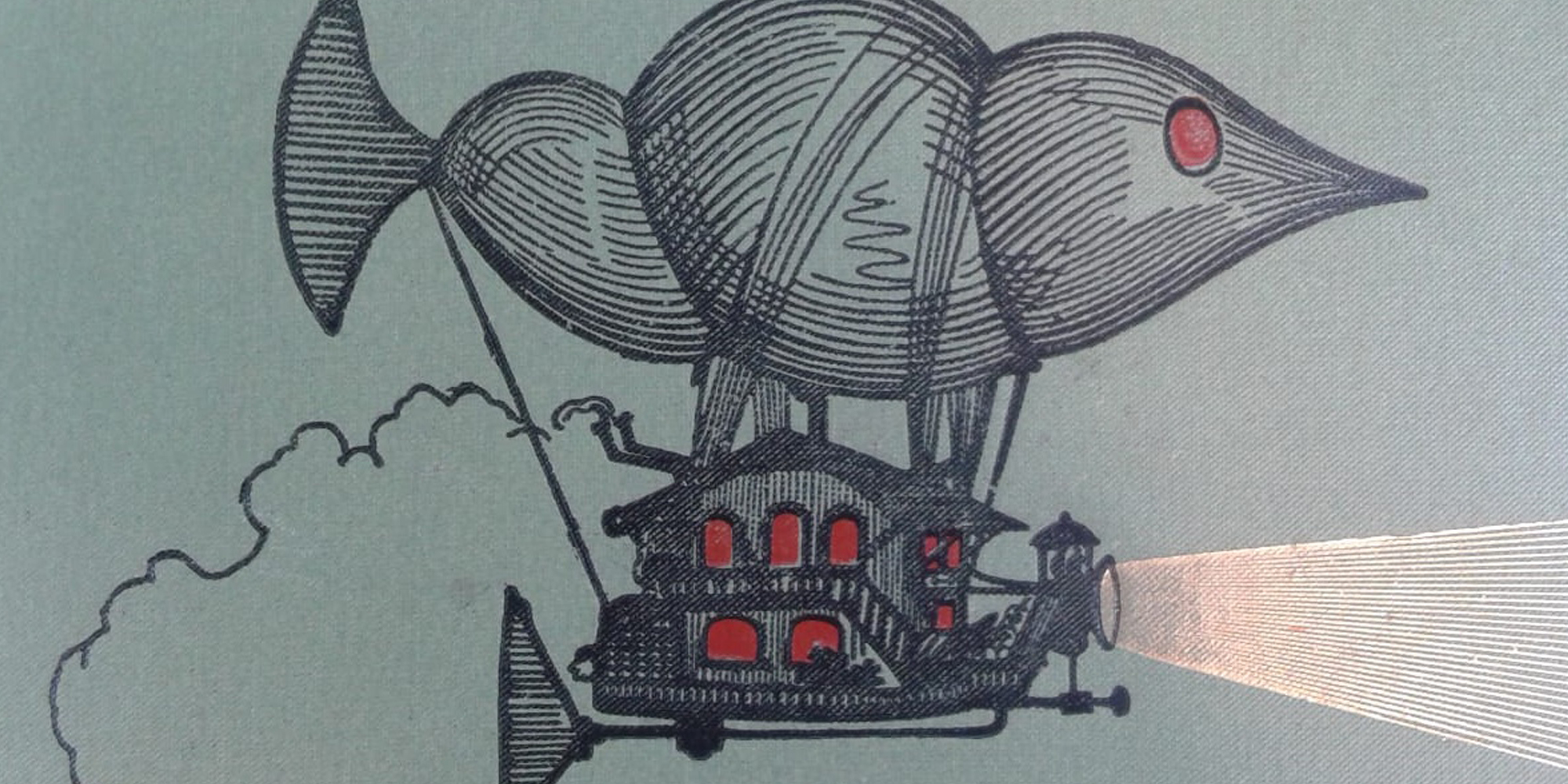

Among the books in our library, there is a fascinating volume titled Le vingtiéme siecle written in 1884 by writer and illustrator Albert Robida. It begins like this:

“The month of September 1952 was drawing to a close. The omnibus airship B, which operated between the central station of the Tubes – boulevard Montmartre – and the aristocratic faubourg Saint-Germaine, was traveling at the regulated altitude of 250 meters. The arrival of the British Tube train quickly filled a dozen airships parked above the station, and sent a swarm of aerotaxis into the air.”

Paris in 1952: neighborhoods suspended in the air, public and private transportation entrusted to airships, connections between cities, and even continents, through trains traveling in underground tunnels, submarines, and advertising balloons.

The world of the future as seen through the dreams of the 19th century. The book is full of brilliant ideas beautifully illustrated by Robida’s pencil sketches.

An electric tramway takes the crowds of visitors from the emerging mass tourism along the exhausting galleries of the Louvre; waitresses are ready with their soup tureens and platters at the entrance of the pipe system that allows for a domestic catering service.

There are also surprising prophetic anticipations: from 1945, it will be possible to subscribe to the Compagnie universelle du Telephonoscope; a crystal plaque embedded on a wall in a home allows entertainment lovers, without leaving their house, to comfortably sit and watch performances from their favorite theaters; it also provides a 24-hour information service about what’s happening in the world and even allows remote video calls to your home.

Social changes are not overlooked, though told with some fear: by 1952, there will be female doctors, notaries, lawyers, prefects, parliamentarians, and journalists: truly science fiction!

An ingenuous optimism fills this representation of the coming century, although there are some concerns related to pollution: a sincere trust in technology and science as harbingers of certain progress in human life. This trust, however, was irreparably shattered by the 20th century as depicted in our book. Orwell’s bleak, hyper-controlled world of 1984, so prophetic regarding our present, the post-nuclear, spectral landscape full of nightmares from the novel

The Road by Cormac McCarthy, or in the cinematic field, the overpopulated city under a constant torrential rain in Blade Runner, tell us with greater truth than our 1970s TV shows about how the 20th century viewed the future, in what has been called the Society of Sad Passions.