Every publishing house has its golden year.

In the “miraculous spring of 1963,” as Ernesto Ferrero defines it in his interesting history of Einaudi [Ernesto Ferrero, I migliori anni della nostra vita, Feltrinelli, 2005], the Turin publishing house published La cognizione del dolore by Gadda, La giornata di uno scrutatore by Calvino, Il Consiglio d’Egitto by Sciascia, Lo scialle andaluso by Morante, Lessico familiare by Ginzburg, Le memorie di Adriano by Yourcenar, and La tregua by Primo Levi.

The years 1957 and 1958 were exceptional years for Feltrinelli.

On October 25, 1958, the novel Il Gattopardo by debutant Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa was published in 3000 copies. The success was overwhelming: by December, two new editions were released, and the novel became the literary sensation of the moment. The author had submitted it to Elio Vittorini to be published in the Einaudi’s Gettoni series, but the manuscript was rejected because it was considered “incompatible with a progressive idea of literature,” to quote Ernesto Ferrero once again. After all, it wasn’t the first time a masterpiece had been rejected by a publishing house for reasons unrelated to its aesthetic-literary value.

Celeste Albaret, the legendary housekeeper of Proust, describes in her memoirs [Celeste Albaret, Monsieur Proust, SE] the writer’s bitterness upon realizing that the string that closed the package containing the manuscript of Du côté de chez Swann had not even been touched. André Gide, assigned by Gaston Gallimard to evaluate the work, knew well that Marcel Proust: a frequent guest of the salons of Faubourg Saint-Germain, a flâneur, an amateur, even quite snobbish; why waste time with him?

Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa was also an “amateur”: the last descendant of an ancient Sicilian noble family, he had published nothing before that mysterious novel. Tomasi di Lampedusa did not live to see it published: it was Elena Croce, after his death, who proposed the manuscript to Giorgio Bassani, the head of Feltrinelli’s Literature Library series. Bassani immediately recognized the masterpiece and had it published. By 1963, from the masterpiece, another masterpiece was born: Luchino Visconti’s incredibly sharp cinematic version. The ballroom scene in the Prince Salina’s palace remains a milestone in the history of cinema.

But Il Gattopardo only “doubles” another sensational editorial success for the Milanese house: and this time, it was not just an Italian first edition, but a worldwide first edition.

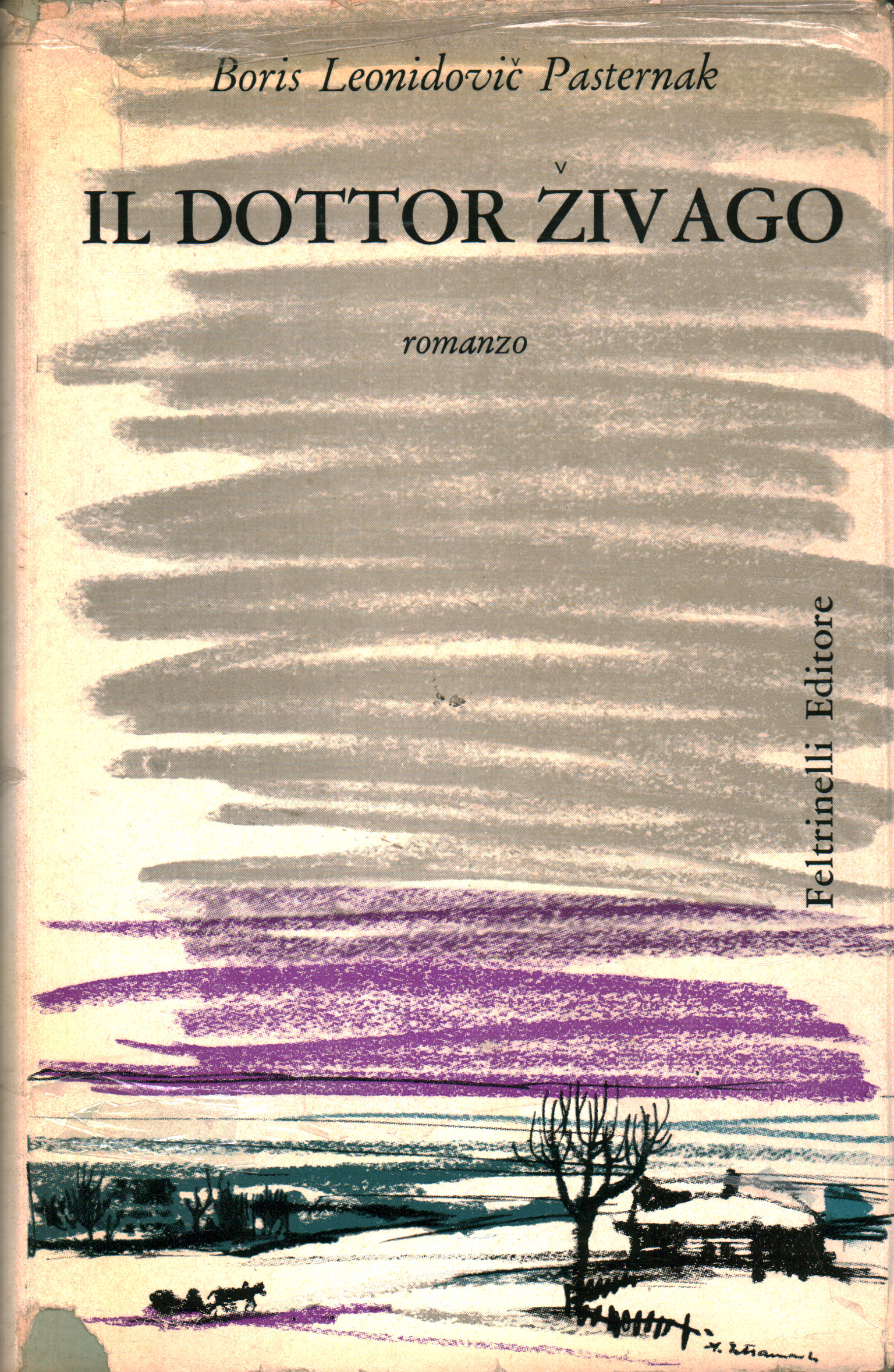

On November 15, 1957, Doctor Zhivago by Boris Leonidovich Pasternak was published.

Until then, Pasternak was known as an avant-garde poet of Soviet Russia, but for years he had been working on this great historical novel. The Publisher’s Note summarizes the editorial story:

“Boris Pasternak finished this book more than 3 years ago. In 1956 and 1957, Soviet radio and the magazine Znamja had announced its upcoming publication in the Soviet Union. Our publishing house, recognizing the value of the Author, secured the publication rights. We thus received the manuscript directly from the author. An agreement was reached that the Italian edition would not be published before September 1957. At the end of summer, when the publication was imminent and nothing indicated that difficulties had arisen in the USSR regarding publication, we were asked by the author to return the manuscript, as he wished to revise it. However, we were unable to comply with the author’s request as the book was already in an advanced stage of preparation. We are therefore presenting to the Italian public this edition in the original version for which publication had been agreed with the author. We believe this edition of Doctor Zhivago not only honors the Author but also the literature to which he belongs.”

The novel, blocked by censorship, was not published in the Soviet Union until 1988, during the Gorbachev era. Only in 1989 could Pasternak’s son retrieve the Nobel Prize that had been awarded to his father in 1958.

A worldwide first edition, therefore, by Feltrinelli, which was followed by countless other editions worldwide.

And naturally, it was also followed by a Hollywood blockbuster in 1965. A whole generation carries in their hearts the memory of Omar Sharif’s languid eyes and the moving Lara’s Theme from the soundtrack.

And indeed, a rare first edition of Doctor Zhivago by Pasternak is present in our online bookstore catalog. A copy that is not perfect, not a sterile bibliophile display copy: a copy that has certainly been well read because it was dearly loved.

P.S. I would like to break a lance in defense of poor, and later deeply mortified, André Gide; I happened to read a collection of articles that Marcel Proust wrote for the social column of Le Figaro before his Recherche days: it is absolutely unrecognizable; an abyss separates these dull and boring reports of matinées and Parisian evenings from the descriptions of the society he frequents in the Recherche, the salons of the Guermantes, radiographed by the sharp and merciless gaze of the Narrator.

Perhaps then, one thing we can learn from this story, we mere mortals, is: never stop at our convictions, always nurture a healthy curiosity towards things. In every person, in every event, a masterpiece can be hidden.